I’ve written before about the importance of cpu cache efficient algorithms. This is yet another adventure in that world. First, however, let’s start with a simple cache quiz: which code is faster?

/* going vertical */

for (x=0;x<width;x++)

for (y=0;y<height;y++)

a[y*width+x] = b[y*width+x] + c[y*width+x]

/* going horizontal */

for (y=0;y<height;y++)

for (x=0;x<width;x++)

a[y*width+x] = b[y*width+x] + c[y*width+x]

The second one. Right? Every programmer knows that the second is faster, and they know why (I hope). A simple matrix addition is simple enough that we can “reason” our way into which is theoretically faster without actually trying it. I recently ran a much more complex example of a similar problem.

The problem: For face recognition, it is often necessary to compute a huge face similarity matrix. Face X compared with face Y returns a score Z. We place Z at (X,Y). It’s a fairly straightforward output to a huge comparison between two sets of faces. The naive method would look very similar to the matrix adds at the top. You start in the upper left corner, do the entire first row, one by one, and then move onto the second row, etc.

The hypothesis: If we break the computation into sub-blocks, it will more effectively use cache and thus be faster. As an example, for a 1000x1000 comparison, the naive method would do all 1000 comparisons in the first row, then 1000 more for the second, and so on. The block method would break the computation into, for example, 100x100 blocks. By only using these sub-blocks, it allows you to use the same input faces more frequently and thus, hopefully, more cache efficiently.

So let’s try it

I took the 20 required minutes, randomly picked a block size (I think it was on the order of 50x50), and lo and behold, it was substantially faster than the naive method. Alright. Now, how do I go about finding a good block size? Unlike our matrix addition example, this is a tough answer to reason your way towards, so I decided to play around to build up some intuition for the problem.

Does block area matter?

Yes, it matters. 2x2 blocks are just too small. There’s too much overhead introduced by breaking the problem into that many blocks (especially with threading enabled). There needs to be enough “meat” in the blocks to make it worth your while.

Are square blocks best?

It seemed like a logical question. It took almost no time for me to figure out that absolutely not, square blocks were not better. The very first test I ran was something along the lines of 50x50 blocks versus 25x100 blocks. The 25x100 blocks crushed the 50x50 blocks. Interesting.

How about the direction of travel?

Which was faster 10x40 or 40x10? Turns out 10x40 was substantially faster than 40x10. This is getting confusing. I spent another hour playing with numbers and eventually came to the conclusion that putting the smallest dimension in the horizontal direction made it faster. Inside the inner function, if a block size comes in that doesn’t follow this rule, I switched them (so if you asked for a block size of 40x10, you got 10x40).

Time to stop screwing around

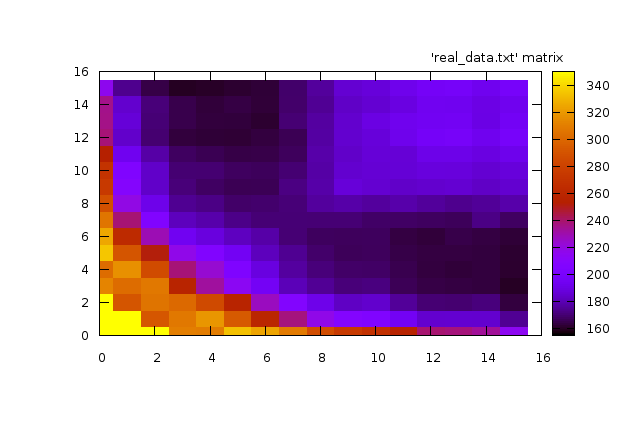

I was about 2 hours into this little adventure when I realized there was absolutely no way I was going to meander to the right answer. This wasn’t a simple problem. The only solution was my old friend science. Let’s actually run the experiment and see what happens. I picked 16 different lengths ranging from 2 to 1000, and ran every permutation of block sizes and graphed the results. Here’s what it looked like:

This graph is just so cool. Let me explain what you are looking at. It’s a 2d plot in a heat-graph format. The darker the color, the faster the code ran. The position in the grid represents the block size. As we travel right along the graph, we are increasing the longer dimension and as we travel upward along the graph, we are increasing the shorter dimension. The diagonal from bottom-left to top-right, then, is the square block sizes. The graph is also symmetric because of the rule I put in to ensure the longer dimension is always height (explained above). This graph has three interesting features:

- The extremely "hot" (slow) region hugging the bottom and the left axes. This region is when one (or both) dimensions is extremely small. With extremely small windows, there's too much overhead (especially with threading) and it begins to dominate the actual computation.

- The bizarre rectangle in the upper-right. More on this in a second.

- The sweet-spot dark regions that essentially correspond to extremely long and fairly skinny rectangles.

Making Sense of it All

That rectangle in the upper right perplexed me and so I showed it around. Someone at the office had a conjecture that sounded plausible (versus my previous theory of plain old black magic). For small widths, the entire horizontal input is able to be cached. As you grow the width, eventually you reach a point where the horizontal input no longer fits, and by the time you start on the next row of the block, the first input is largely gone. In other words, my little graph shows quite clearly the moment that our block blows up our cache.

That particular theory meant, then, that the point where the block was “too” wide depended heavily on the machine and the environment the process was running. Since I didn’t want to tune too much to a single machine, I thought it wise to avoid going anywhere near that line.

My final block-size selection algorithm looks something like this: Use as tall a rectangle as is reasonable, make it as skinny as possible such that you ensure there is enough area to drown out threading overhead.

Measure. Measure. Measure.

At the end of the day, you can pretty much “explain” any cache behavior, once you’ve seen it. You can find a plausible reason why certain things make the code run faster. Maybe in hindsight your explanation will even makes sense. Its become obvious to me, however, that for any non-trivial problem, you positively need to rigoriously experiment.

© louis brandy — theme: midnight by mattgraham — with help from jekyll bootstrap and github pages